Data Visualization & Digital Humanities

Anne Boleyn’s Tudor Networks

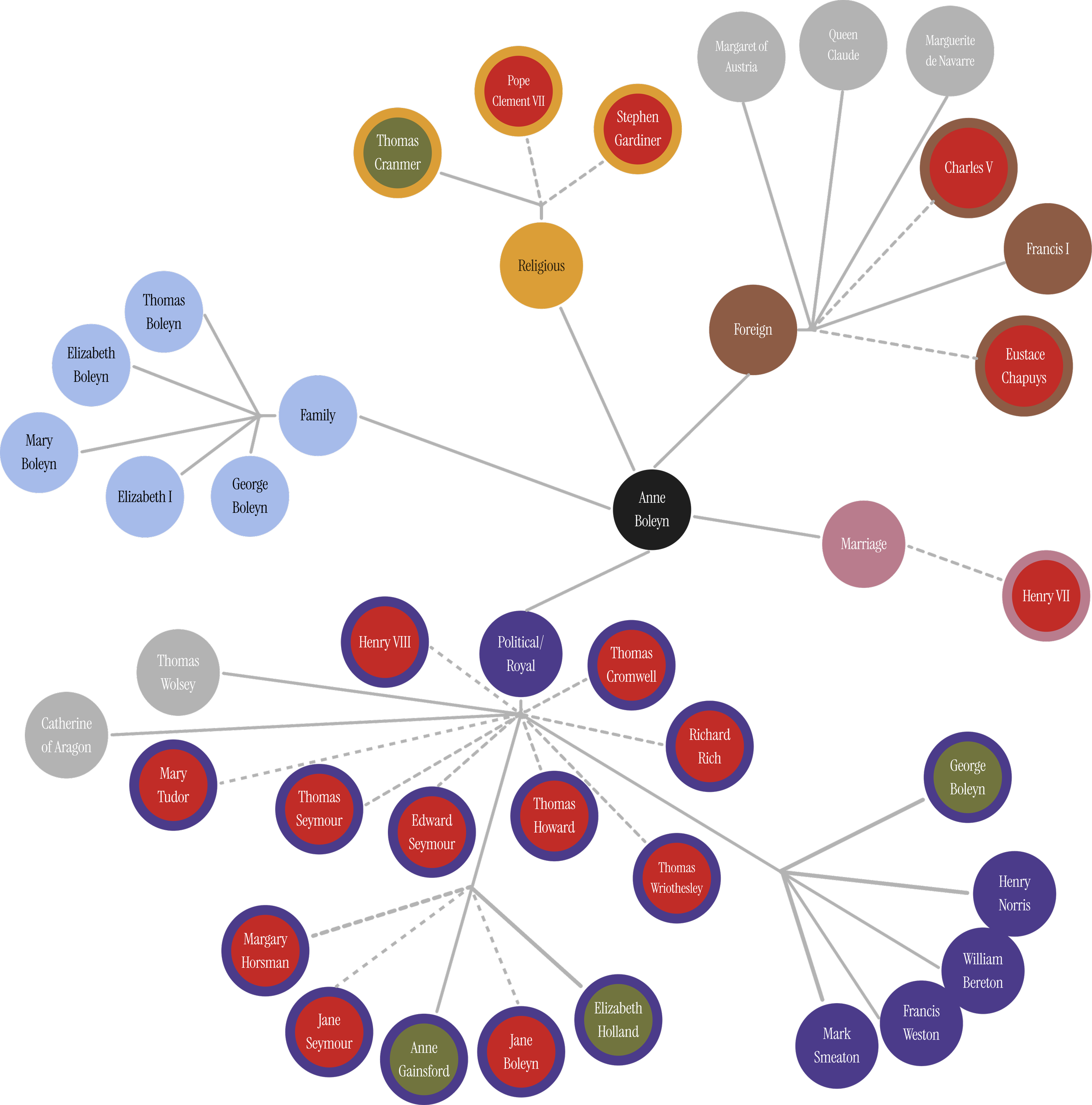

This project aims to visually represent the way in which Anne Boleyn moved through her social world, focusing on the evolution and impact of her network, and how this shaped periods of her life.

Why Anne Boleyn?

I’ve always been interested in Tudor history, specifically the women of this period. After reading Hillary Mantel’s Wolf Hall trilogy, I became particularly fascinated by Anne Boleyn. I wanted to gain a better understanding of who Anne was outside of her relationship with Henry VIII. She was unusually outspoken and confident for a woman of this time, and so I wanted to take a deep dive into her early life. I thought that by uncovering how she moved through the world, and identifying who she came in contact with in her formative years, I might be able to paint a more complete picture of how Anne’s life was shaped by the social worlds of the Tudor period.

Tudor Networks

Tudor England relied heavily on social networks to assign power, and these networks revolved around King Henry VIII - the closer to Henry, the higher the social standing.

However, gaining proximity to the King did not ensure safety or security.

This is particularly evident in the case of Anne Boleyn. Through network visualizations, this project seeks to shine a light on the connections that Anne Boleyn made throughout her life.

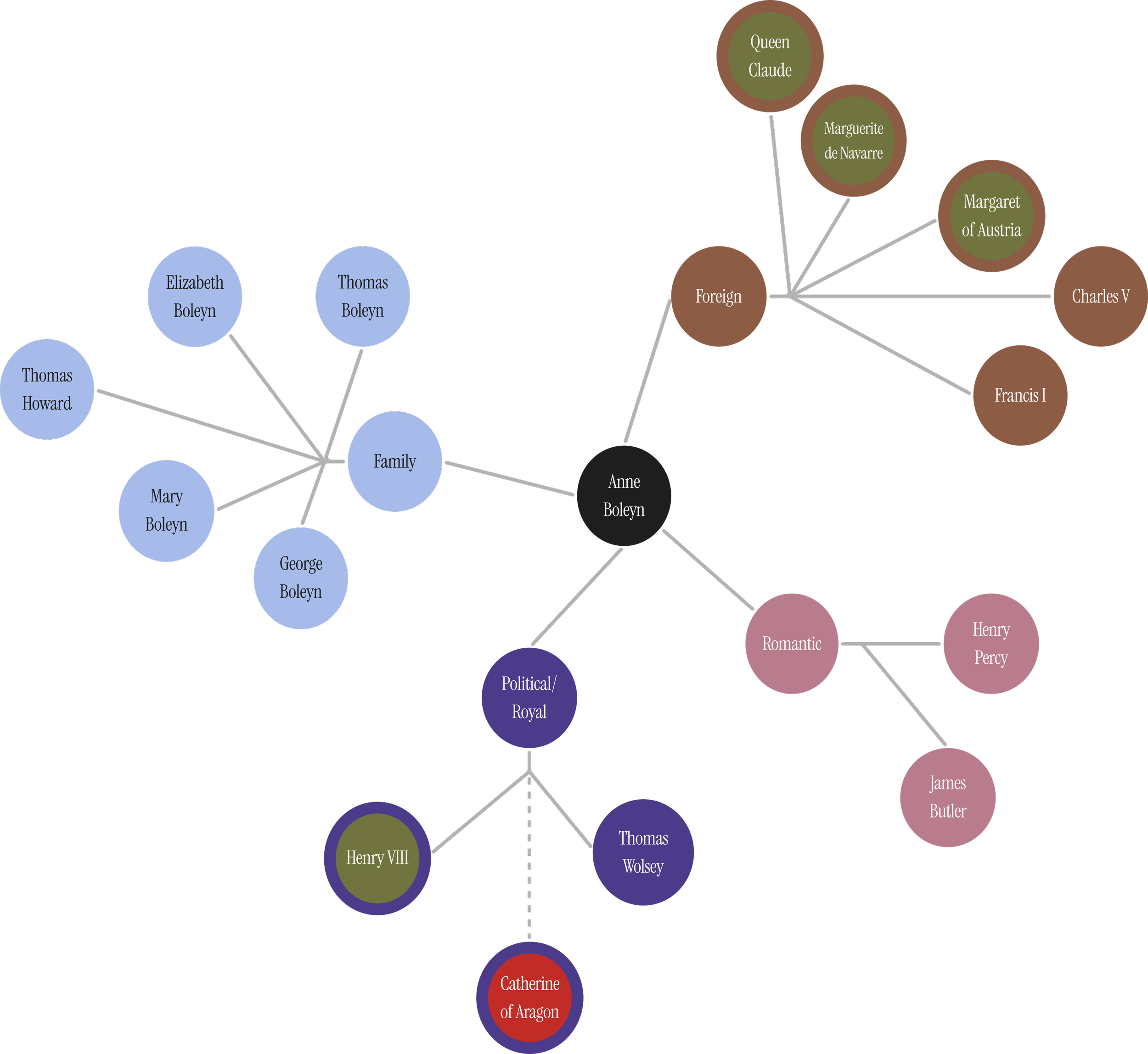

1513-1526

*Opposition does not necessarily reflect a connection’s personal feelings towards Anne, but instead represents how certain individuals were compelled to take this side either for their own political gain, safety, religious views, or as a matter of circumstance.

Around 1513, Anne Boleyn left England for the Netherlands. Anne joined the Court of Savoy in Mechelen as a maid of honor for Margaret of Austria. At this time, Anne was just a teenager.

The most notable connections Anne made during this time were with the powerful female figures whose courts she served. The regent of the Netherlands, Margaret of Austria was a strong ruler and a highly skilled diplomat, and to a young Anne Boleyn, she potentially served as a powerful model of female agency.

In 1514, Anne moved to France to become an attendant to Queen Claude. Anne went on to spend seven years in France, and some historians believe that during this time Anne came in contact with Queen Claude’s sister-in-law Marguerite de Navarre, who’s support of religious reform potentially influenced Anne’s own beliefs on the subject.

In 1521, Anne moved back to England to serve Queen Catherine of Aragon. At this time, Anne’s father Thomas was appointed Treasurer of the Royal Household; this high-ranking position put him in direct contact with the King.

By 1526, Henry VIII had noticed Anne Boleyn at court and began writing love letters asking her to become his mistress. Anne refused his offer - if Henry wanted a relationship with her, he would have to obtain it through marriage.

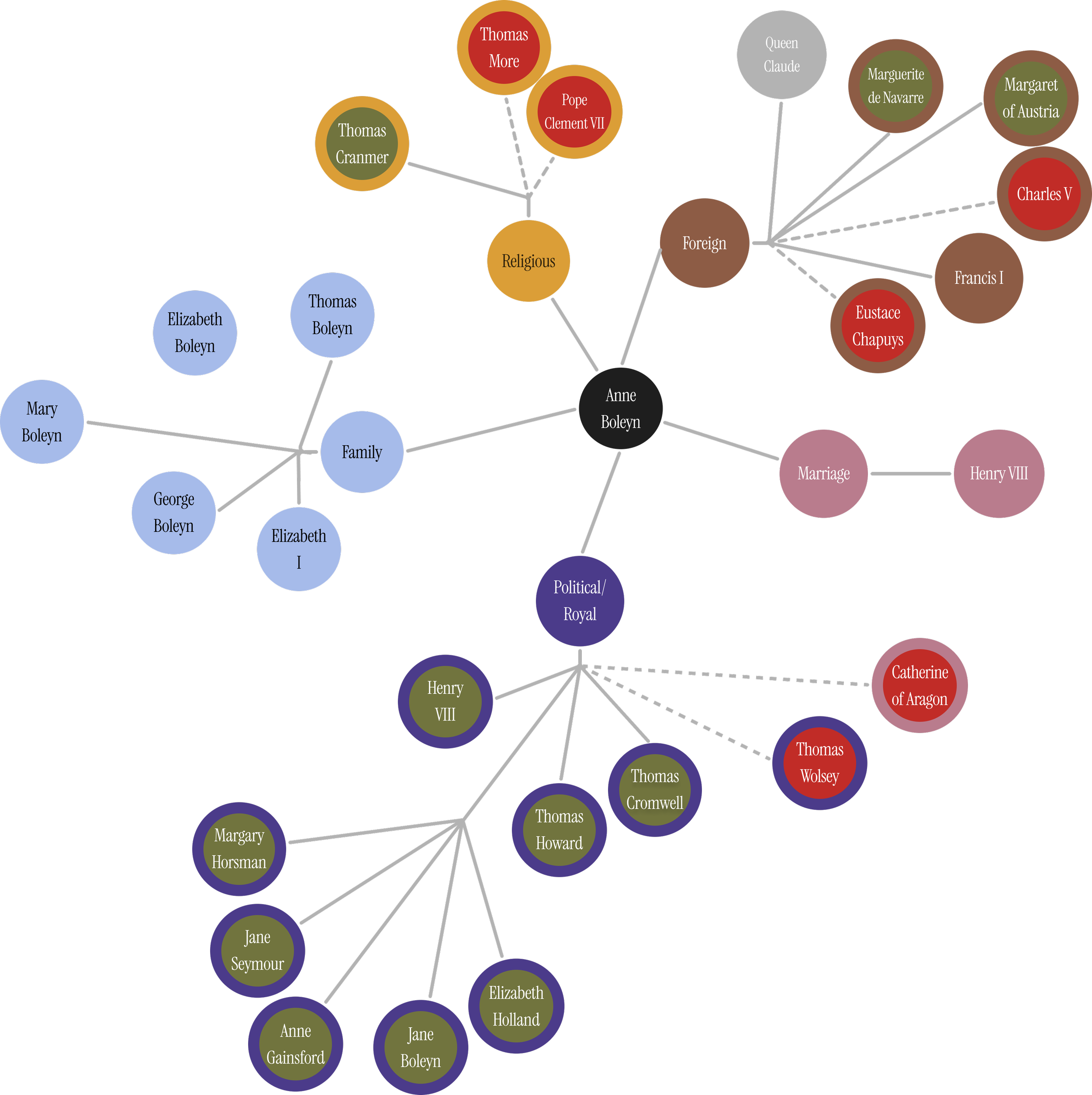

1526-1533

During this time, Anne and Henry were engaged in a lengthy period of courtship, facing many roadblocks on their path to marriage. They weren’t officially married until January of 1533.

One notable connection of Anne’s during this period of time was Thomas Cranmer. As a direct result of Anne’s influence over Henry, he was appointed Archbishop of Canterbury in 1533, shortly before Anne and Henry’s public marriage. As Archbishop, Cranmer was able to legitimize Anne and Henry’s marriage and expedite the annulment of Henry and Catherine of Aragon’s marriage. He also supported Anne’s religious efforts in the English Reformation, as he also held reformist beliefs.

Anne enjoyed an initially strong relationship with Thomas Cromwell, one of Henry’s chief advisers.

One of Anne’s main adversaries during this time period was Catherine of Aragon, who refused to acknowledge the annulment of her marriage. This impacted the legitimacy of Anne’s queenship, and was further complicated by the fact that Catherine of Aragon was a popular Queen. As a result, Anne was not widely accepted by the public.

Anne also faced challenging relationships with religious conservatives, like Thomas More, the Lord Chancellor. He opposed Henry and Anne’s marriage and refused to swear an oath which acknowledged the Act of Succession in 1534. Swearing an oath to this act meant recognizing Anne Boleyn as Henry’s lawful wife, More also refused to acknowledge Henry as the Supreme Head of the Church in England. As a result, More was charged with treason and executed at the Tower of London on July 6, 1535.

1513-1526

As Anne’s marriage to Henry VIII faltered, so did her network of connections. After Anne suffered a series of miscarriages and failed to produce the male heir which Henry greatly desired, he began courting one of Anne’s ladies-in-waiting, Jane Seymour.

By this period, Thomas Cromwell was Henry’s Chief Minister. Anne and Cromwell’s relationship had been strained by an ongoing disagreement regarding how to use the wealth that had been taken from the Catholic Church. Then, in 1536, Henry — driven by his desire for a new marriage — ordered Cromwell to procure an annulment from Anne. Cromwell, wanting to ensure a complete break from Anne, orchestrated her arrest for high treason by alleging that she committed adultery with the courtiers Henry Norris, William Bereton, Francis Weston, and court musician Mark Smeaton. Cromwell even went as a far as to accuse Anne of also engaging in an incestuous affair with her brother.

Sensing her fall from favor, powerful court figures such as her uncle Thomas Howard, started distancing themselves from Anne. Others used the period of instability in her marriage to further malign Anne, like Eustace Chapuys (the Imperial Ambassador).

Anne was executed on May 19th, 1536, two days after her brother George and the four others. The trial was widely believed to have been a sham with little no evidence for the charges brought against Anne.